13 Short Horror Novels: edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh (Collected 1987), containing the following stories:

"Jerusalem's Lot" (1978) by Stephen King: Fun riff by King on Lovecraft's horror stories, most obviously "The Rats in the Walls", told through a series of letters. Has nothing to do with 'Salem's Lot.

"The Parasite" (1894) by Arthur Conan Doyle: The creator of Sherlock Holmes indulges his love of the paranormal, specifically hypnotism, here. Boy, people thought hypnotism (or 'mesmerism') could do some crazy stuff in the 19th century. Here it allows for the telepathic takeover of other people's bodies!

"Fearful Rock" (1939) by Manly Wade Wellman: Excellent Civil War period piece from Wellman, as a patrol of Union soldiers finds itself confronted with supernatural evil.

"Sardonicus" (1961) by Ray Russell: Classic story from Russell is a blackly humourous character study written in a 19th-century epistolary style. Made into a movie called Mr. Sardonicus.

"Nightflyers" (1980) by George R. R. Martin: Once upon a time, the Game of Thrones creator was an excellent horror and science fiction writer. He combines the two here for a locked-room-in-space horror show. Made into a terrible movie of the same name.

"Horrible Imaginings" (1982) by Fritz Leiber: Weird, relatively late-career novella from the great Leiber riffs much more grimly on his years in San Francisco after his wife's death than similar works of the same period that include "The Ghost Light" and Our Lady of Darkness. Not great, but spellbinding nonetheless, with a completely bizarre conclusion.

"Jane Brown's Body" (1938) by Cornell Woolrich: Interesting combination of the horror and hard-boiled crime-fiction genres. Gangsters, mad scientists, and a tragic ending you know is coming, as inevitable as death in a world where death has been temporarily conquered.

"Killdozer!" (1944) by Theodore Sturgeon: Sturgeon goes full-on Basil Exposition here as he explains pretty much everything you ever wanted to know about how to operate a bulldozer and a backhoe. I kid you not. There's pages and pages of handy bulldozer operation knowledge here. An interesting premise (an electromagnetic monster takes over a bulldozer; hilarity obviously ensues) bogs down in interminable explanations of how everything works. If you're fascinated by the heavy machinery of 1944, this novella is for you. Made into a movie of the same name.

"The Shadow Out of Time" (1936) by H. P. Lovecraft: One of Lovecraft's least horrifying, most science-fictiony and sublime meditations on cosmic stuff and time abysses. The aliens here -- 12-foot-tall rugose cones dubbed "the Great Race" -- are probably Lovecraft's least threatening, most benign race of super-aliens. Also, they're socialists.

"The Stains" (1980) by Robert Aickman: Aickman is at his creepy, ambiguous best here in a story of a buttoned-down widower who starts a new life with a young woman who is...well, I don't know. Baffling, oblique, and utterly haunting, but not for anybody who wants some sort of minimal explanation of what is actually happening.

"The Horror from the Hills" (1931) by Frank Belknap Long: Gonzo Exposition from Long's Gonzo Exposition Cosmic Horror Period that also yielded such distinctive, Lovecraft-lecture-series gems as "The Space-Eaters" and "The Hounds of Tindalos." A man-sized, vaguely elephant-shaped idol comes to life and threatens all life on Earth. And only a museum director, a cop, and an occult inventor can save us in a final battle staged in...New Jersey! Paging Jules de Grandin!

"Children of the Kingdom" (1980) by T. E. D. Klein: I've read this novella at least ten times over the course of 32 years and find something new to ponder every time. This time around, it's the fact that in this story of racism and xenophobia in the decaying, crime-ridden New York of the late 1970's, the ultimate horrors that move literally beneath the surface are fish-belly white.

"Frost and Fire" (1946) by Ray Bradbury: Disquieting and propulsive bit of science-fiction-as-metaphor by Bradbury, as humans stranded on a highly radioactive planet by a spaceship crash are born, age, and die in the space of eight days (!). A telepathy mutation allows the children to rapidly learn, but can one determined man find a way to reach the last extant starship and find a way off the planet?

Horror stories, movies, and comics reviewed. Blog name lifted from Ramsey Campbell.

Friday, August 23, 2013

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Weird!

Weird Tales Volume 1 edited by Peter Haining, containing the following stories: The Man Who Returned by Edmond Hamilton; Black Hound of Death by Robert E. Howard; The Shuttered House by August Derleth; Frozen Beauty by Seabury Quinn; Haunting Columns by Robert E. Howard; Beyond the Wall of Sleep by H. P. Lovecraft; The Garden of Adompha by Clark Ashton Smith; Cordelia's Song by Vincent Starrett; Beyond the Phoenix by Henry Kuttner; The Black Monk by G. G. Pendarves; Passing of a God by Henry S. Whitehead; and They Run Again by Leah Bodine Drake (1923-1939; collected 1978):

Solid anthology (well, the first half of a hardcover anthology, divided for paperback publication) of stories from the first 15 years of Weird Tales, the pulp magazine that got its start in 1923. This half is quite heavy on the novella-length story, with lengthy entries from Robert E. 'Conan' Howard, Seabury Quinn, Henry Kuttner, and Henry S. Whitehead.

The Howard piece is an interesting, intensely racist story of supernatural revenge set in the two-fisted South. Kuttner's story features his sword-and-sorcery hero Elak of Atlantis. Seabury Quinn's supernatural detective Jules de Grandin tackles Bolsheviks and suspended animation in a fairly un-supernatural outing.

Solid shorter stories come from H.P. Lovecraft, August Derleth, and Edmond Hamilton (the latter Quinn's only real rival for the title of 'Most popular writer among the then-readers of Weird Tales). Clark Ashton Smith's entry is a grotesque humdinger. And the now-little-known Henry S. Whitehead contributes a truly bizarre piece about voodoo and...stomach tumours??? It's not a tumour!!! Recommended.

Solid anthology (well, the first half of a hardcover anthology, divided for paperback publication) of stories from the first 15 years of Weird Tales, the pulp magazine that got its start in 1923. This half is quite heavy on the novella-length story, with lengthy entries from Robert E. 'Conan' Howard, Seabury Quinn, Henry Kuttner, and Henry S. Whitehead.

The Howard piece is an interesting, intensely racist story of supernatural revenge set in the two-fisted South. Kuttner's story features his sword-and-sorcery hero Elak of Atlantis. Seabury Quinn's supernatural detective Jules de Grandin tackles Bolsheviks and suspended animation in a fairly un-supernatural outing.

Solid shorter stories come from H.P. Lovecraft, August Derleth, and Edmond Hamilton (the latter Quinn's only real rival for the title of 'Most popular writer among the then-readers of Weird Tales). Clark Ashton Smith's entry is a grotesque humdinger. And the now-little-known Henry S. Whitehead contributes a truly bizarre piece about voodoo and...stomach tumours??? It's not a tumour!!! Recommended.

Science!

Frankenweenie: written by Tim Burton, Leonard Ripps, and John August; directed by Tim Burton; starring the voices of Catherine O'Hara (Mrs. Frankenstein/Weird Girl/Gym Teacher), Martin Short (Mr. Frankenstein/Mr. Burgemeister/Nassor), Martin Landau (Mr. Rzykruski), Charlie Tahan (Victor Frankenstein), and Winona Ryder (Elsa Van Helsing) (2012): Enjoyable black-and-white cartoon fom Burton, in the animation style of other Burton-produced projects such as Corpse Bride and The Nightmare Before Christmas. The whole thing is based on Burton's first short film for Disney back in the 1980's, before he got his first feature directorial gig on Pee Wee's Big Adventure. How time flies!

Burton and his writers recast Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as a suburban horror-comedy in the vein of Edward Scissorhands. Frankly, it could be the exact same street. Copious references abound to movie monsters from Boris Karloff's Creature to Gamera the flying turtle. One of the oddities of the movie is that it offers a heartfelt plea for science education, painting anti-science citizens as dangerous loons.

The whole thing is set in New Holland, which while it has nothing really to do with Frankenstein novel or film, does apparently resemble Burton's childhood home. Perhaps more importantly, New Holland also allows for an explanation of why there's an oldey-timey windmill around to stage the climax within. Because Tim Burton loves windmills (though it's also an homage to the 1930's Karloff Frankenstein movies).

All in all, breezy and enjoyable and surprisingly non-misanthropic. And much, much better than a lot of Burton's recent live-action films. The reanimated dog is a real charmer. I'm still trying to figure out if the Dutch can sue for national defamation. Recommended.

Man on a Ledge: written by Pablo F. Fenjves; directed by Asger Leth; starring Sam Worthington (Nick Cassidy), Anthony Mackie (Mike Ackerman), Jamie Bell (Joey Cassidy), Genesis Rodriguez (Angie), Titus Welliver (Dante Marcus), Elizabeth Banks (Lydia Mercer), and Ed Harris (David Englander) (2012): Enjoyable heist film that's easy on the brain. Sam Worthington again makes for a somewhat bland protagonist, as he did in Avatar and Clash of the Titans. Ed Harris is suitably wormy as a Donald Trump-like real-estate mogul who frames cop Worthington for a crime he didn't commit. Genesis Rodriguez's bustline plays a major supporting role. Lightly recommended.

Burton and his writers recast Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as a suburban horror-comedy in the vein of Edward Scissorhands. Frankly, it could be the exact same street. Copious references abound to movie monsters from Boris Karloff's Creature to Gamera the flying turtle. One of the oddities of the movie is that it offers a heartfelt plea for science education, painting anti-science citizens as dangerous loons.

The whole thing is set in New Holland, which while it has nothing really to do with Frankenstein novel or film, does apparently resemble Burton's childhood home. Perhaps more importantly, New Holland also allows for an explanation of why there's an oldey-timey windmill around to stage the climax within. Because Tim Burton loves windmills (though it's also an homage to the 1930's Karloff Frankenstein movies).

All in all, breezy and enjoyable and surprisingly non-misanthropic. And much, much better than a lot of Burton's recent live-action films. The reanimated dog is a real charmer. I'm still trying to figure out if the Dutch can sue for national defamation. Recommended.

Man on a Ledge: written by Pablo F. Fenjves; directed by Asger Leth; starring Sam Worthington (Nick Cassidy), Anthony Mackie (Mike Ackerman), Jamie Bell (Joey Cassidy), Genesis Rodriguez (Angie), Titus Welliver (Dante Marcus), Elizabeth Banks (Lydia Mercer), and Ed Harris (David Englander) (2012): Enjoyable heist film that's easy on the brain. Sam Worthington again makes for a somewhat bland protagonist, as he did in Avatar and Clash of the Titans. Ed Harris is suitably wormy as a Donald Trump-like real-estate mogul who frames cop Worthington for a crime he didn't commit. Genesis Rodriguez's bustline plays a major supporting role. Lightly recommended.

Sunday, August 11, 2013

The Horrors of the 'Me' Decade

Whispers II: edited by Stuart David Schiff, containing the following stories:

Undertow by Karl Edward Wagner; Berryhill by R. A. Lafferty; The King's Shadow Has No Limits by Avram Davidson; Conversation Piece by Richard Christian Matheson; The Stormsong Runner by Jack L. Chalker; They Will Not Hush by James Sallis and David Lunde; Lex Talionis by Russell Kirk; Marianne by Joseph Payne Brennan; From the Lower Deep by Hugh B. Cave; The Fourth Musketeer by Charles L. Grant; Ghost of a Chance by Ray Russell; The Elcar Special by Carl Jacobi; The Box by Lee Weinstein; We Have All Been Here Before by Dennis Etchison; Archie and the Scylla of Hades Hole by Ken Wisman; Trill Coster's Burden by Manly Wade Wellman; Conversation Piece by Ward Moore; The Bait by Fritz Leiber; Above the World by Ramsey Campbell; The Red Leer by David Drake; and At the Bottom of the Garden by David Campton.

Stuart David Schiff's Whispers was the biggest little magazine of horror and dark fantasy in the 1970's, so much so that it became the Little Engine That Carried on The Tradition of the Mostly Defunct Weird Tales. Schiff couldn't pay a lot, but with weird fantasy markets in decline, he was able to assemble a Who's Who of then-contemporary greats, with careers sometimes extending back to the 1920's and 1930's.

Whispers II collects fine stories by names familiar and unfamiliar. I've got a real soft spot for David Drake's revisionist werewolf tale "The Red Leer," which also seems to act as a commentary on the sorts of manly men who once frequented the horror stories of Robert E. Howard. There really aren't any weak spots here, though Ken Wisman's "Archie and the Scylla of Hades" is bizarre in both tone (it's like a Jack Vance fantasy story as reimagined by Robert Service) and style (it's a long poem!). When you see these Whispers compilations in used bookstores, you should snap them up. Along with editor Charles L. Grant's hardcover original anthology series Shadows, Whispers represents the height of 1970's and early 1980's dark fantasy and horror. Highly recommended.

Tales of Fear and Fantasy by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, containing the following stories: Manderville; The Day Of The Underdog; The Headless Footman Of Hadleigh; The Cost Of Dying; The Resurrectionist; The Sale of the Century; and The Changeling (Collected 1977): Chetwynd-Hayes was amazingly prolific in the late 1960's and early 1970's. His learning curve was dramatically steep: six years after the release of his first, enjoyable, pulpy collection, this collection shows a writer rounding into top form.

Five of the stories mix horror with black comedy, with the most successful being one of the adventures of "the world's only practicing psychic detective" as he and his lovely, extremely psychic assistant try to solve the mystery of "The Headless Footman of Hadleigh." There are two non-humourous stories here, and they're both hauntingly excellent: "The Resurrectionist", in which a man falls in love with photos of a woman long dead, and "The Changeling", a creepy riff on pop-culture 'horror families' such as The Munsters or The Addams Family. This family, though, not so much fun to belong to. In all, recommended.

Undertow by Karl Edward Wagner; Berryhill by R. A. Lafferty; The King's Shadow Has No Limits by Avram Davidson; Conversation Piece by Richard Christian Matheson; The Stormsong Runner by Jack L. Chalker; They Will Not Hush by James Sallis and David Lunde; Lex Talionis by Russell Kirk; Marianne by Joseph Payne Brennan; From the Lower Deep by Hugh B. Cave; The Fourth Musketeer by Charles L. Grant; Ghost of a Chance by Ray Russell; The Elcar Special by Carl Jacobi; The Box by Lee Weinstein; We Have All Been Here Before by Dennis Etchison; Archie and the Scylla of Hades Hole by Ken Wisman; Trill Coster's Burden by Manly Wade Wellman; Conversation Piece by Ward Moore; The Bait by Fritz Leiber; Above the World by Ramsey Campbell; The Red Leer by David Drake; and At the Bottom of the Garden by David Campton.

Stuart David Schiff's Whispers was the biggest little magazine of horror and dark fantasy in the 1970's, so much so that it became the Little Engine That Carried on The Tradition of the Mostly Defunct Weird Tales. Schiff couldn't pay a lot, but with weird fantasy markets in decline, he was able to assemble a Who's Who of then-contemporary greats, with careers sometimes extending back to the 1920's and 1930's.

Whispers II collects fine stories by names familiar and unfamiliar. I've got a real soft spot for David Drake's revisionist werewolf tale "The Red Leer," which also seems to act as a commentary on the sorts of manly men who once frequented the horror stories of Robert E. Howard. There really aren't any weak spots here, though Ken Wisman's "Archie and the Scylla of Hades" is bizarre in both tone (it's like a Jack Vance fantasy story as reimagined by Robert Service) and style (it's a long poem!). When you see these Whispers compilations in used bookstores, you should snap them up. Along with editor Charles L. Grant's hardcover original anthology series Shadows, Whispers represents the height of 1970's and early 1980's dark fantasy and horror. Highly recommended.

Tales of Fear and Fantasy by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, containing the following stories: Manderville; The Day Of The Underdog; The Headless Footman Of Hadleigh; The Cost Of Dying; The Resurrectionist; The Sale of the Century; and The Changeling (Collected 1977): Chetwynd-Hayes was amazingly prolific in the late 1960's and early 1970's. His learning curve was dramatically steep: six years after the release of his first, enjoyable, pulpy collection, this collection shows a writer rounding into top form.

Five of the stories mix horror with black comedy, with the most successful being one of the adventures of "the world's only practicing psychic detective" as he and his lovely, extremely psychic assistant try to solve the mystery of "The Headless Footman of Hadleigh." There are two non-humourous stories here, and they're both hauntingly excellent: "The Resurrectionist", in which a man falls in love with photos of a woman long dead, and "The Changeling", a creepy riff on pop-culture 'horror families' such as The Munsters or The Addams Family. This family, though, not so much fun to belong to. In all, recommended.

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Pulpy Goodness in Bite-Sized Chunks

The Unbidden by R. Chetwynd-Hayes, containing the following stories: No One Lived There; Why Don't You Wash? Said The Girl With œ100,000 And No Relatives; Don't Go Up Them Stairs; The Gatecrasher; A Family Welcome; Crowning Glory; The Devilet; Come To Me My Flower; The Playmate; Pussy Cat - Pussy Cat; A Penny For A Pound; The Head Of The Firm; The Treasure Hunt; The Death Of Me; Tomorrow Is Judgement Day; and The House (Collected 1971):

The prolific English horror and science-fiction writer R. Chetwynd-Hayes (possibly the most English writer's name of all time) came to professional writing fairly late, at about 40, but made up for lost time with fairly astounding productivity. His high point of fame probably came when a movie, The Monster Club, was adapted from several of his short stories.

I certainly wouldn't argue that he was a great writer, or sometimes even a very good one, but many of his ideas are fascinating. He also brought a black sense of humour to many of his stories. The horrors tend to the supernatural, though not exclusively, and many of his stories are so droll as to leave horror altogether for the sort of dark whimsy that Roald Dahl specialized in when he wasn't writing children's novels.

This collection, the first for Chetwynd-Hayes, is an enjoyable and quick read. Some of the stories deliver ironic supernatural vengeance upon evil-doers ("Why Don't You Wash? Said The Girl With œ100,000 And No Relatives", "A Penny For A Pound"), some visit horror upon the innocent and unlucky ("Come To Me My Flower", "Pussy Cat - Pussy Cat", "The Playmate"), some play as weird comedy ("Don't Go Up Them Stairs", "The Head Of The Firm"), and the final story, "The House", offers gentle fantasy rather than horror. Recommended.

The prolific English horror and science-fiction writer R. Chetwynd-Hayes (possibly the most English writer's name of all time) came to professional writing fairly late, at about 40, but made up for lost time with fairly astounding productivity. His high point of fame probably came when a movie, The Monster Club, was adapted from several of his short stories.

I certainly wouldn't argue that he was a great writer, or sometimes even a very good one, but many of his ideas are fascinating. He also brought a black sense of humour to many of his stories. The horrors tend to the supernatural, though not exclusively, and many of his stories are so droll as to leave horror altogether for the sort of dark whimsy that Roald Dahl specialized in when he wasn't writing children's novels.

This collection, the first for Chetwynd-Hayes, is an enjoyable and quick read. Some of the stories deliver ironic supernatural vengeance upon evil-doers ("Why Don't You Wash? Said The Girl With œ100,000 And No Relatives", "A Penny For A Pound"), some visit horror upon the innocent and unlucky ("Come To Me My Flower", "Pussy Cat - Pussy Cat", "The Playmate"), some play as weird comedy ("Don't Go Up Them Stairs", "The Head Of The Firm"), and the final story, "The House", offers gentle fantasy rather than horror. Recommended.

Bar Sinister

I Wear the Black Hat (Grappling with Villains Real and Imagined) by Chuck Klosterman (2013): The always entertaining pop-culture essayist Klosterman delivers a book-length meditation on how current American society decides who its fictional and real-life villains are, and why.

Klosterman loves to set up binary and trinary constructions as if they were the only possible ways to approach a problem ("There are two explanations for this..."), which aids in making the book a source of argument and debate. It's a lot like a really good and really rambling discussion one would have in a bar with someone more versed in popular culture than in the philosophy and literature of the past. There's a faint structure here, but for the most part this reads like about 15 essays on one topic, and not a coherent whole.

Many of the topics are fun and interestingly argued. And the occasional shagginess of the structure contributes to the feeling of this being a terrific bar conversation, wandering a bit as all bar conversations do. And the strongest section of the book, an examination of Batman as related to Bernard Goetz, spawns the best relatively new idea for a movie or comic-book representation of Batman that I've come across in a long, long time.

Also fascinating and bizarre is Klosterman's comparison of O.J. Simpson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as public "villains", especially as Klosterman discusses Simpson's bizarre "tell-all", If I Did It, which may be one of the few books in history to belong to a sub-sub-genre completely unique to itself.

Has anyone else in history tried and acquitted of murder subsequently written a memoir in which he or she convincingly and graphically describes the actual murder as a hypothetical in a memoir otherwise presented as factual? And was said memoir taken away from the autobiographicist prior to release and given to the family of one of the murder victims so that they could attempt to raise funds with its publication? Klosterman manages something extraordinary here: he makes me want to read O.J.'s book. Well, almost. Recommended.

Klosterman loves to set up binary and trinary constructions as if they were the only possible ways to approach a problem ("There are two explanations for this..."), which aids in making the book a source of argument and debate. It's a lot like a really good and really rambling discussion one would have in a bar with someone more versed in popular culture than in the philosophy and literature of the past. There's a faint structure here, but for the most part this reads like about 15 essays on one topic, and not a coherent whole.

Many of the topics are fun and interestingly argued. And the occasional shagginess of the structure contributes to the feeling of this being a terrific bar conversation, wandering a bit as all bar conversations do. And the strongest section of the book, an examination of Batman as related to Bernard Goetz, spawns the best relatively new idea for a movie or comic-book representation of Batman that I've come across in a long, long time.

Also fascinating and bizarre is Klosterman's comparison of O.J. Simpson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as public "villains", especially as Klosterman discusses Simpson's bizarre "tell-all", If I Did It, which may be one of the few books in history to belong to a sub-sub-genre completely unique to itself.

Has anyone else in history tried and acquitted of murder subsequently written a memoir in which he or she convincingly and graphically describes the actual murder as a hypothetical in a memoir otherwise presented as factual? And was said memoir taken away from the autobiographicist prior to release and given to the family of one of the murder victims so that they could attempt to raise funds with its publication? Klosterman manages something extraordinary here: he makes me want to read O.J.'s book. Well, almost. Recommended.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

The Lost Alan Moore Episode

Fashion Beast: adapted by Antony Johnson from the screenplay by Alan Moore based on a screen story by Malcolm McLaren and Alan Moore; illustrated by Fecundo Percio (2012-2013): Alan Moore's lost project, a 1985 screenplay for a never-produced movie, based on a story by music and fashion impresario Malcolm McLaren, here gets adapted into a 200-page+ graphic novel. The redoubtable Antony Johnson handles the actual adaptation, as he has for other non-comic-book Moore work adapted into comic-book form.

Artist Fecundo Percio really draws up a storm here. The art remains relatively representational throughout with two exceptions -- the creepy, wizened monkey-women who are the guardians of the gates of Celestine, a fashion house in a future New York. America fights a war against somebody never named. Fallout is everywhere. The world is collapsing.

And that's only the background to this reimagining of the story of Beauty and the Beast, gene-spliced with elements from McLaren's own life and with Moore's taste for outre philosophy.

Beauty would appear to be Doll Seguin, a transvestite whom we first meet dressed like Marilyn Monroe and working as a coat-check 'girl' at the Cabaret, a stylish blend of dance hall and performance space. The Beast may be fashion-designer Celestine, never seen by anyone but the guardians of the gates, giving his approval or diapproval to auditioning models from behind smoked glass. Or it may be Jonni, a butch, aspiring fashion designer who longs to overthrow the concealing, antisexual fashions of House Celestine and put in their place the freer, more liberated fashions she herself has designed.

And that's just the set-up of the first two issues, after which things get really weird.

Johnson preserves the distinctive style and structure of mid-1980's Alan Moore -- this really is of a piece with Watchmen and 'V' for Vendetta, a sharp and cynical work of action-philosophy over which looms the spectre of nuclear armageddon. It's involving and fascinating on its own. But it also adds to the fictional over-structure of Alan Moore's 1980's work in a pleasing, off-beat way. And Percio's art, as with the art of David Lloyd on 'V' and Dave Gibbons on Watchmen, works beautifully with Moore's colourful, metaphorical, expositional prose by providing it with a solid, seemingly representational counterpoint. Highly recommended.

Artist Fecundo Percio really draws up a storm here. The art remains relatively representational throughout with two exceptions -- the creepy, wizened monkey-women who are the guardians of the gates of Celestine, a fashion house in a future New York. America fights a war against somebody never named. Fallout is everywhere. The world is collapsing.

And that's only the background to this reimagining of the story of Beauty and the Beast, gene-spliced with elements from McLaren's own life and with Moore's taste for outre philosophy.

Beauty would appear to be Doll Seguin, a transvestite whom we first meet dressed like Marilyn Monroe and working as a coat-check 'girl' at the Cabaret, a stylish blend of dance hall and performance space. The Beast may be fashion-designer Celestine, never seen by anyone but the guardians of the gates, giving his approval or diapproval to auditioning models from behind smoked glass. Or it may be Jonni, a butch, aspiring fashion designer who longs to overthrow the concealing, antisexual fashions of House Celestine and put in their place the freer, more liberated fashions she herself has designed.

And that's just the set-up of the first two issues, after which things get really weird.

Johnson preserves the distinctive style and structure of mid-1980's Alan Moore -- this really is of a piece with Watchmen and 'V' for Vendetta, a sharp and cynical work of action-philosophy over which looms the spectre of nuclear armageddon. It's involving and fascinating on its own. But it also adds to the fictional over-structure of Alan Moore's 1980's work in a pleasing, off-beat way. And Percio's art, as with the art of David Lloyd on 'V' and Dave Gibbons on Watchmen, works beautifully with Moore's colourful, metaphorical, expositional prose by providing it with a solid, seemingly representational counterpoint. Highly recommended.

Saturday, August 3, 2013

Imitations of Life

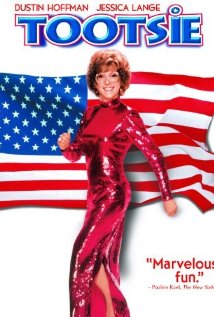

Tootsie: written by Larry Gelbart, Murray Schisgal, Don McGuire, Robert Garland, Barry Levinson, and Elaine May; directed by Sydney Pollack; starring Dustin Hoffman (Michael Dorsey/Dorothy Michaels), Jessica Lange (Julie), Teri Garr (Sandy), Dabney Coleman (Ron), Bill Murray (Jeff), Charles Durning (Les), George Gaynes (John Van Horn), Geena Davis (April) and Sidney Pollack (George Fields) (1982): Ah, what a great comedy. The cast is terrific and in fine form in this fable of an actor (Hoffman) who learns to be a better man by pretending to be a woman in order to get a job on a soap opera.

It's really remarkable how zingy the dialogue is throughout, and how uniformly excellent is the cast (including director Pollack as Hoffman's long-suffering agent). The difficulty of working with Hoffman forms a subtext to the entire picture -- Pollack refused to direct him again despite Tootsie's massive critical and commercial success. Bill Murray drifts in and out to provide a loose, improvisational Greek Chorus as Hoffman's playwright-room-mate, Jessica Lange won an Oscar for her sweet, funny performance, and everyone else is also awesome. Highly recommended.

The Mummy: written by Jimmy Sangster; directed by Terence Fisher; starring Peter Cushing (John Banning), Christopher Lee (Kharis the Mummy), and Yvonne Furneaux (Isobel/Ananka) (1959): Enjoyable, atmospheric remake by British Hammer Studios of the original 1930's Universal horror movie The Mummy. This movie completed Christopher Lee's Hammer trifecta of playing three of the four classic horror-movie monsters originally made famous by those Universal movies of the 1930's -- Dracula, Frankenstein's Monster, and the Mummy, but alas, no Wolf Man.

Lee hated the heavy make-up and costuming for the Mummy, and would avoid heavy make-up ever afterwards. Like Karloff before him, he towers over the rest of the cast (there's a funny moment in which a drunk English poacher claims that the Mummy is 10-feet tall, and it doesn't seem like that much of an exaggeration). Lee is again teamed with his Dracula and Frankenstein co-star Peter Cushing, here playing the son of the archaeologist who released the vengeful mummy into the world.

The Egyptian sets and costumes are really quite impressive, as are the moody scenes set on the moor and in the swamp nearby, with some nice staging for scenes in which the Mummy emerges from, and later descends into, the swamp. Cushing makes for an interesting hero here as he did in the Dracula films as Van Helsing, and Yvonne Furneaux is lovely in the dual role of Cushing's wife and the long-dead Egyptian priestess Ananka, whom Lee's high priest loved and was ultimately mummified alive for loving.

Lee does what he can with his eyes, the only expressive part his made-up face shows, and by the end achieves a sort of lurching, Frankensteinian pathos as the Mummy. That pathos is also partially obtained by having a cultist give the Mummy his murderous orders. The Mummy really looks like he'd rather not stir from his 4000-years' sleep. Recommended.

It's really remarkable how zingy the dialogue is throughout, and how uniformly excellent is the cast (including director Pollack as Hoffman's long-suffering agent). The difficulty of working with Hoffman forms a subtext to the entire picture -- Pollack refused to direct him again despite Tootsie's massive critical and commercial success. Bill Murray drifts in and out to provide a loose, improvisational Greek Chorus as Hoffman's playwright-room-mate, Jessica Lange won an Oscar for her sweet, funny performance, and everyone else is also awesome. Highly recommended.

The Mummy: written by Jimmy Sangster; directed by Terence Fisher; starring Peter Cushing (John Banning), Christopher Lee (Kharis the Mummy), and Yvonne Furneaux (Isobel/Ananka) (1959): Enjoyable, atmospheric remake by British Hammer Studios of the original 1930's Universal horror movie The Mummy. This movie completed Christopher Lee's Hammer trifecta of playing three of the four classic horror-movie monsters originally made famous by those Universal movies of the 1930's -- Dracula, Frankenstein's Monster, and the Mummy, but alas, no Wolf Man.

Lee hated the heavy make-up and costuming for the Mummy, and would avoid heavy make-up ever afterwards. Like Karloff before him, he towers over the rest of the cast (there's a funny moment in which a drunk English poacher claims that the Mummy is 10-feet tall, and it doesn't seem like that much of an exaggeration). Lee is again teamed with his Dracula and Frankenstein co-star Peter Cushing, here playing the son of the archaeologist who released the vengeful mummy into the world.

The Egyptian sets and costumes are really quite impressive, as are the moody scenes set on the moor and in the swamp nearby, with some nice staging for scenes in which the Mummy emerges from, and later descends into, the swamp. Cushing makes for an interesting hero here as he did in the Dracula films as Van Helsing, and Yvonne Furneaux is lovely in the dual role of Cushing's wife and the long-dead Egyptian priestess Ananka, whom Lee's high priest loved and was ultimately mummified alive for loving.

Lee does what he can with his eyes, the only expressive part his made-up face shows, and by the end achieves a sort of lurching, Frankensteinian pathos as the Mummy. That pathos is also partially obtained by having a cultist give the Mummy his murderous orders. The Mummy really looks like he'd rather not stir from his 4000-years' sleep. Recommended.